Vision Zero at 10: Bill de Blasio Looks Back in an Exclusive Interview

No single New Yorker is as connected to Vision Zero as Bill de Blasio, the mayor who launched the initiative in 2014. There was definitely some vision in the policy, but not the “zero” part, with deaths of pedestrians and cyclists remaining more or less constant. So we chatted with de Blasio about his singular legacy.

Streetsblog: What policies and interventions do you think were most effective during your time as mayor and pursuing Vision Zero?

Bill de Blasio: I would say with no fear of contradiction, I don’t know one of them that wasn’t. To me, lowering speed limits, speed cameras, traffic redesigns — they all contributed. Queens Boulevard is by far my most beloved example, because it was so horrible, and the change is so positive and profound.

And the other thing that, really, I didn’t understand about Vision Zero in the beginning is how much it changes behavior. It’s not just the functional reality of each encounter that a motorist has with enforcement, or cameras, etc., but it sensitizes everyone to think very differently about the relationship with their cars and trucks. It’s been a profound educational tool, I think, that keeps growing. The behavioral change dynamic is much greater than I thought it would be, and I’m thrilled about that. I think that is achieved by all of the pieces, and the constant reinforcement.

What impediments do you still see, to this day, getting in the way of that policy work?

Most of the challenges are in Albany, in my humble opinion. You know, the city needs even greater freedom to place speed cameras as it chooses and for whatever period of time it chooses. And then we need much tougher laws in terms of reckless motorists and the consequences of their actions.

What type of tougher laws are you speaking about?

Motorists can cause a lot of harm and feel very little penalty. There just needs to be a constant tightening up the consequences when someone’s injured or someone’s killed. But also, obviously the case of repeat offenders, folks who speed incessantly and get to keep their license and get to keep the car. The laws and the enforcement are still not strong enough to show people that that’s unacceptable — that there’s unacceptable behaviors that result in very, very firm consequences. That’s what I think is missing.

Eighty percent of people get the message from speed cameras, when they get the first ticket. Then there’s a separate group of people who either can afford to pay or just sort of don’t care and will keep offending over and over again. It seems like we’ve had a lot of trouble reaching those people in particular.

I just don’t think the enforcement is consistent. To be fair, it takes a lot of resources to enforce. You know, it’s not automatic. But I think it’s a worthy investment. In some ways, it can pay for itself if enforcement yields greater fine recovery, but really beyond the economics, the laws just aren’t strong enough. And I think, NYPD and the Taxi and Limousine Commission would happily enforce stronger laws. But, you know, there’s no equivalent of three strikes and you’re out. … It seems to me that when people realize some of these outcomes are automatic, that’s when behavior changes more. To some extent, we’ve seen that with speeding cameras, but I think in terms of the reckless drivers who think they can speed incessantly and keep their car or keep their license, I just think the culture right now is that you can get away with it. We need laws that are so firm and so undebatable in the minds of folks who are thinking the wrong thing, that it will start to affect behavior.

Did the NYPD buy into the importance of traffic enforcement?

At the highest levels, very much so. Ten years ago when we announced it, Bill Bratton was an extremely energetic partner. He was at that point, unquestionably, the most prominent police leader in America. For him to embrace it so wholeheartedly was very, very helpful. And everyone I worked with at the top levels of the NYPD felt the same way.

Now, you can say, “Well, what about the average officer or average precinct commander?” I don’t have enough of a vantage point on that, but I do know that it’s all about resource allocation. And when the message comes from the top to put more of the time into enforcement, it’s a paramilitary organization, they’re going to do it. But the challenge was always the competing needs.

The origin story, for me, of Vision Zero, the reason we committed so deeply to it was seeing the number of crashes and number of traffic fatalities rise up to the level almost of the number of murders. That was the wake-up call that we have to really reorient a lot of our energy and focus. That equation has been disrupted by the pandemic and the surge in gun violence that resulted. We’re now coming back down to Earth. We’re now getting back to a lot of the reality of pre-pandemic, and I think this is the time to reassess how much energy, how much resources and personnel, goes into traffic enforcement. Once that order is given from on high, of course, the precinct commander, so the rank-and-file will follow it.

Do you think there’s a limit to this idea that reducing traffic deaths should be a major policy?

What was very striking as we rolled out Vision Zero the first couple of years was how much the public embraced it — how much it was clear, and this was [due to] incredible efforts by organizations like Families for Safe Streets, that the public understood this meant children, this meant seniors, this could happen to them and their family. I don’t think that’s changed. And I will tell you that each challenge we face is different in terms of how you approach. Like, the opioid crisis is very, very difficult to address because it’s so individual — whereas addressing traffic safety is something that we’ve proven we can do on a really big level, very effectively. And we’ve only just started, I mean, a decade’s nothing. There’s a lot more to go.

I think you can sustain interest in Vision Zero and keep it building. I broadly believe the public understands it’s been a success, notwithstanding the disruptions of COVID. And it’s cumulative. Every time you do a traffic redesign, that has an ongoing effect, and there’s so many more to do. And again, we haven’t had the enforcement we would have ideally liked for the last four years. The other challenges will always be very real and sometimes, as with gun violence, of course, there will be a need to disproportionately invest police resources when we see a surge in gun violence. But in more normal times — and certainly consistent that the first six years of my administration, pre-pandemic — we had the opportunity to shift resources into traffic safety, and it had a real impact and people saw it. That track record is going to help in terms of sustaining public interest and public support for Vision Zero.

In a recent interview about Vision Zero, you cited overcoming community opposition to these traffic redesigns. I definitely saw that on Skillman Avenue and Queens Boulevard, when the community board came out strong and you sort of put your foot down and said “No, the safety priority is more important here.” But it was always an uphill struggle, and I think it continues to be an uphill struggle for DOT in the current administration, which says it wants more community engagement and outreach. Is there a way to get beyond and above that type of dynamic?

This is just a tough reality. We have to be honest about this. We saw this with Vision Zero, we saw this with placement of homeless shelters. In the end, democracy certainly involves consultation. I think it’s very healthy. There were traffic redesigns and bike lanes that community members objected to and offered real feedback — real, honest, and helpful feedback that led to alterations. That’s good, that’s healthy. God bless the DOT, but sometimes, you know, in the the lab, as it were, something looks great on paper, and then out in the community proves to be more problematic.

And community members or community leaders or elected officials who say, “Hey, can we adjust this? Can we do this differently? How about we do this street instead of that street?” That’s good, that’s healthy. But in the end, the executive branch has to guarantee the safety of New Yorkers. So I think, healthy, energetic consultation — and at times, I think we did that, at times I think they could have done it better. I certainly commend Ydanis Rodriguez because he comes from grassroots work, people want to listen. But you listen, you think about it, you weigh it, and then you still have to move forward. That was the reality of Queens Boulevard. People had objections, we weighed them, and decided that they did not alter the fundamental reality that we had an extremely dangerous street, we had lost so many people, and we needed to do something very different.

So I don’t think consultation has to equal paralysis. And it’s different than the situation where, for example, you need a City Council vote. And the local council member, in land use, for example, has a particular impact. That’s different than something like a traffic redesign where, in my view, you take the input, you take it seriously, and then you make the decision, you move forward.

I’m wondering what you think might account for differences in Vision Zero outcomes for majority white and majority non-white communities?

I do think there might be some pieces of this that correlates to where car ownership is greater, car usage is greater. And that obviously tends to be farther out in the boroughs. I think it does correlate to some demographic realities. So that could be part of it. But I would argue, only without going without seeing the details, and obviously, being deeply concerned about equity, that Vision Zero is still in its infancy. If there need to be serious adjustments made, there’s plenty of ability to do that.

Now, I will tell you, I’ve also heard from people over the last few years, in my administration and since, and from people from a variety of demographic communities complaining about speed cameras and suggesting that they were biased in their application, or just a way of making revenue. And I just couldn’t be clearer about saying that’s not true. You know, speed cameras are there to save lives. I’m not in office, but I’m speaking as a as a New Yorker, it’d be wonderful if the cameras made no revenue because no one was speeding.

I can understand why motorists don’t like speed cameras. Back in the day, it happened to me a few times, I didn’t like it. But they work. They change behavior, they save lives. And I think that’s the kind of thing that should be applied anywhere where there’s a particular danger. And hopefully, when we look at all these pieces, make sure that we’re always enforcing equity in the equation.

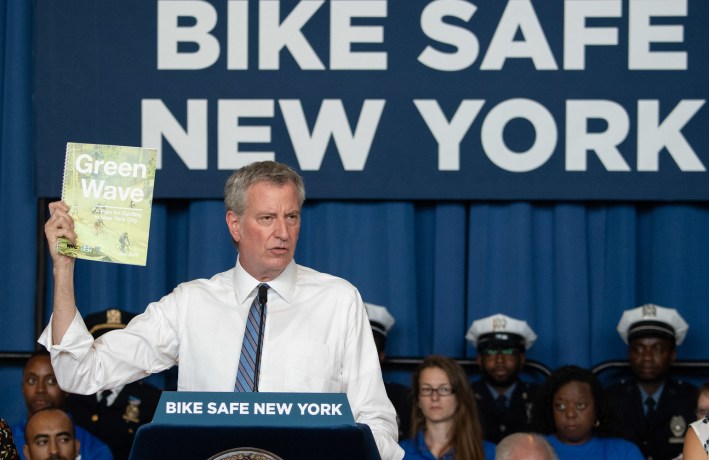

I’ve been thinking a lot about the 2018 “Green Wave” plan, which, as you might recall, was in response to a surge in cyclists deaths. And in general, I felt in your time as mayor, when you received criticism from advocates, you tended to be pretty responsive to it. Advocates have had a different relationship with the current mayor. I’m not asking you to comment specifically on the current mayor, but I’m wondering if you have any advice to the advocacy world, or thoughts about how the advocacy world can deal with a situation where maybe the administration is not as bought into the ideas of Vision Zero as yours was?

I do have a respect and a sympathy for community activism. That’s in my roots. So I do think it gives me the ability to question myself, and sometimes the critiques rang true. Sometimes I thought they were unfair, that’s fine. You know, you can listen to people and call them as you see them. But I think it’s good to listen.

The advice I would say is that the human stories are incredibly powerful, and they helped us make big changes with Vision Zero. I feel horrible for all the families who lost a child, lost a loved one, but they did an incredible job educating legislators, in particular, and making changes possible. I think we need more of that.

I think we also just need more grassroots organizing in terms of making it a front-burner issue to more everyday New Yorkers, because — I was a City Council member — you can tell when your community cares about something. In the trajectory of Vision Zero, I would say sometimes I felt like there was a real, completely local, energetic feeling for it. For example, on Queens Boulevard, you got strong views on both sides, but people were engaged. In some places I didn’t feel like it was it was registering as much.

The challenge for advocates and activists is to go labor in the vineyards and move people and convince them. And even when dozens or certainly hundreds of community residents start to care about issue, a City Council member will feel that pretty quickly. Most of what I feel both about local politics and about national politics is go back to the people. It’s not a magic formula, it’s a lot of what we used to call shoe leather. It’s a lot of knocking on doors, it’s a lot of talking to people outside supermarkets, at subway stations and bus stops, and getting people to feel it and make their feelings known. And that really, really matters..

Is there a different way to sell Vision Zero besides this sort of tragedy-based advocacy?

First of all, whether it’s using the painful examples to wake people up, or whether it’s offering a positive vision of a safer city, or both, I would say, those are all important parts of the equation. I think this movement has achieved a lot. I remember way, way back when, when I first went into City Council, you know, I didn’t even understand some of the mindset, and I got educated and I saw the next 20 years of impact. It’s very impressive. But you never rest on your laurels. And people, even if their minds are changed for a period of time, that doesn’t mean it’s permanent. You have to keep going back to them. Every movement has to be careful not to just talk to itself, or the true believers, and constantly engage people who are undecided or people who are sympathetic, but not yet not yet activated. A positive message, a tough message, a combination, you know, they all have impact. But what it is not necessarily having enough is the kind of community engagement to build critical mass. That’s my two cents.

Do you have any thoughts on how the city can reduce car ownership going forward? Are there more ambitious things that you think the city could pursue in that regard?

I think the simplest way to think about it — realistic and simple right now — is to constantly improve mass transit. As a constant subway user, I would say the subways are a lot more reliable than they used to be. Obviously, all those infusions of funds helped. I think there’s more to go obviously, with Select Bus Service and busways and things that make the bus more appealing. There’s a massive opportunity, which I tried to act on several times, but I didn’t have the most conducive dynamics in Albany in the governor’s mansion. Now hopefully it’s better. I think the NYC Ferry has been a huge success [and] should be expanded over time, but what’s really going to be the breakthrough is when a single fare gets you subway, bus, ferry — any combination. When you make mass transit ever more convenient and effective and frequent, people change their behavior.

Is there room to make, I don’t know, parking more expensive, driving more difficult?

I wouldn’t say that’s the emphasis. You know, I think congestion pricing, which as you know originally I had a lot of concerns about, but that came to be a believer in, is a big adjustment for folks. I think it’s the right policy, but it’s going to be a big adjustment. I don’t think this is about constantly searching for the next financial penalty. I think it’s about providing a solution. And we’re already a great mass transit city, but we definitely can go farther. That’s where I’d focus, you know, the energy and the resources.

Are there any other ideas or thoughts, or suggestions, you have for Vision Zero this next decade?

I think to talk about its next decade. The point is that it’s a revolutionary idea that worked beyond our wildest dreams. I have a critique of progressives, as a progressive, that we are really bad at celebrating our victories and really good at being upset or defeatist. You know, we have a singular victory in Vision Zero. This is something that — we’re talking about the United States of America and the love affair with the automobile for 100 years. And we came along and took an idea from another continent and applied it radically in the biggest city in the country. And people actually bought into it. And it changed behavior. It worked and grew. And it’s not perfect, but it is a stunning start. The first decade could hardly have gone better compared to what you could have projected originally. I worried a lot in the beginning that the knee-jerk opposition would swamp it, and kind of undermine the ability to grow. But it’s been the opposite. It’s become something people have grown accustomed to in a positive way. So my attitude would be, let’s celebrate that and let’s project ahead a decade and going a lot farther, just building on the tools we have. And showing that we can make those numbers much better and that means a lot more lives saved. Like let’s set that aspiration and energize people around it.

I think advocates are really confused and stumped right now, because there’s a big emphasis on the reactionary and reactive voices who are now upset that the street design has changed, and there’s more bikes and more e-bikes. I just think it’s a harder dynamic to work in when your victories have also created more enemies, for lack of a better word.

Yeah. But I think it’s important to speak to. When we started Vision Zero, the notion of ubiquitous e-scooters and e-bikes didn’t exist. And it has complicated the equations. And we do need better approaches to safety. And there are some in this movement who are very resistant to anything they think would discourage e-bike or e-scooter usage. I disagree with that. I think there’s some what we might call common-sense safety measures that would help calm down what’s happening with e-bikes and e-scooters to give people more confidence — pedestrians first, in their ability to be safe.

And that will open the door to more belief and support for the other measures that need to be taken with Vision Zero. So I think sometimes there’s a purism in activism where, you know, because an e-bike or a scooter is not a car, it will be treated as sacrosanct. Or even a traditional bicycle, it’ll be treated as sacrosanct. You can’t do enforcement, you can’t do licenses, you can’t do anything because somehow that’s violating some sure vision of how to provide an alternative. I think that’s backfired. I think what you need right now is to show the public, particularly folks who are pedestrians and feel vulnerable, that we’re really putting safety first and we’re treating all forms of transportation the same way. They all have to go through be treated to a safety prism. I think we do that meaningfully. It opens the door to much more interest in deepening Vision Zero.

Vigorous enforcement and visible enforcement is needed to start to calm things down. This is all about traffic-calming, I don’t care what form the traffic takes, if we want calming, we should want calming across the board. And we want people to feel safe — to not just you know, have statistics and tell them they’re safe, but actually feel safe.

source https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2024/02/15/vision-zero-at-10-bill-de-blasio-looks-back-in-an-exclusive-interview

Comments

Post a Comment