The Other Reason American Pedestrian Deaths are Rising After Dark

On Monday, New York Times asked a question that sustainable transportation advocates have been answering for decades: “Why Are So Many American Pedestrians Dying At Night?”

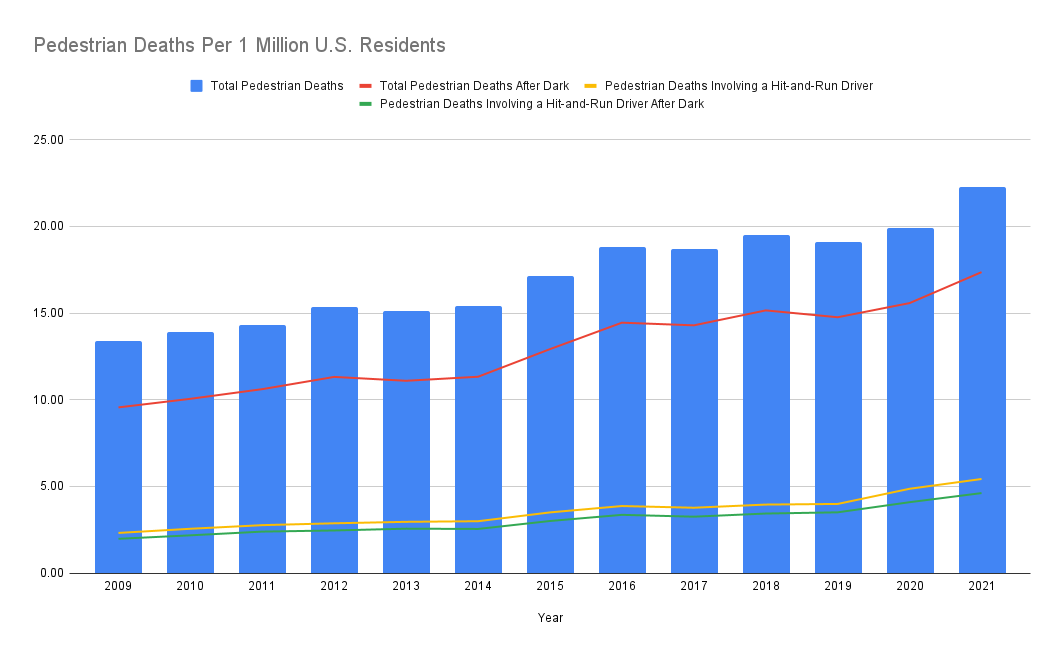

To the Gray Lady’s credit, the article got a lot of things right. Authors Emily Badger, Ben Blatt and Josh Katz correctly explained that the near-doubling of nighttime pedestrian deaths between 2009 and 2021 is the result of a thorny mess of systemic factors, none of which is exclusively responsible for the problem, and few of which are easily solved.

For instance, the writers correctly called out the rising prevalence of SUVs and pick-ups on the road, while keeping in perspective that even right-sizing the nation’s vehicle fleet would prevent about 100 deaths a year. They beautifully explained how the suburbanization of poverty and increases in homelessness have increasingly forced more low- and no-income people to walk on dangerous roads built for vehicle speed rather than their survival. And they even helped contextualize why the rise of the smartphone has proved so much more distracting in the U.S. than it has in Europe, where the continued prevalence of the manual transmission is giving drivers at least some reason to keep their hands off their devices and their eyes on the road.

And the Times journalists acknowledged that “American roads also weren’t particularly engineered with this risk in mind” — namely, because so many of them lack even basic streetlights.

One factor the Times didn’t mention, though, is how the dwindling number of walkers on our roads may itself be contributing to the nation’s fatality rates — and how much worse the death tolls look when seen in the context of how little Americans walk.

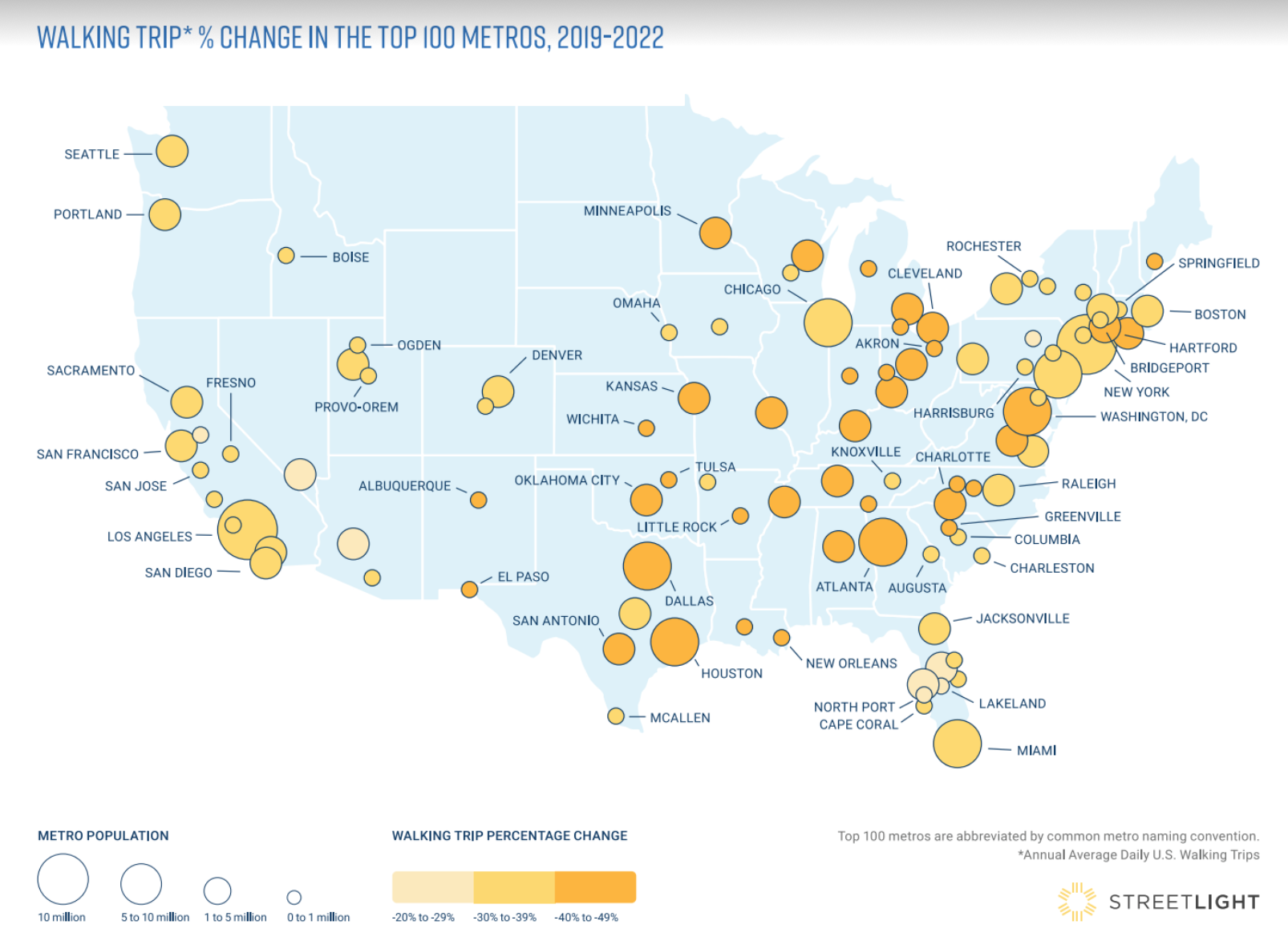

For instance: between 2019 and 2022 alone, big mobility data company Streetlight found that U.S. walking trips had plunged 36 percent after America emerged from quarantine — but walking deaths increased about 20 percent over the same period. And that phenomenon didn’t may not have begun during the COVID era: based on national household travel surveys, at least, America reported five times as many pedestrian deaths per mile than the U.K. did between 2016 and 2018, and 10 times as many deaths as the Netherlands. And those gaps are about twice as large as they were at the turn of the millennium.

As hard as this kind of data is to find — and considering how extensively we document car throughput by comparison, it is maddeningly difficult — evidence is mounting that in many U.S. communities, the humble pedestrian is becoming an endangered species, particularly during the dark night-time hours when three-quarters of walking deaths happen. And because walkers are generally safer in numbers, thinning that herd can have deadly consequences for anyone who remains.

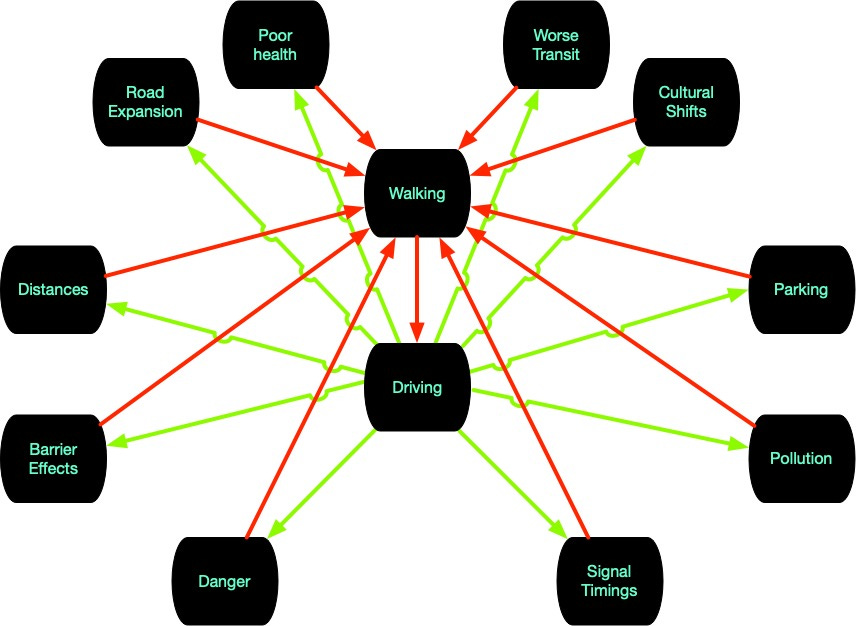

Traffic engineer David Levinson has referred to this phenomenon as the “cycle of unwalkability,” wherein “the presence of cars worsens the conditions of pedestrians; worse conditions for pedestrians reduces walking; reduced walking increases the use of cars; repeat.”

And that vicious cycle isn’t just about walkers being scared off of sidewalks by near-miss crashes and clouds of vehicle smog. It’s about transportation leaders claiming there’s “just no demand” for safe walking infrastructure when they see so few walkers around; it’s about developers building homes further and further out on the fringe for customers who simply “prefer” to drive an hour to work every day; it’s about public transit budgets being slashed to make space on the balance sheet for more “popular” highway projects.

And in time, Levinson argues, the cycle of unwalkability sinks in even deeper. Eventually, many residents of unwalkable places become unable to walk because of sedentary lifestyle diseases that can all too easily set in when they don’t have the time, resources, or motivation to drive to a gym or a park. Meanwhile, others come to authentically love their cars and the culture that surrounds them, and to believe that walking is inherently undesirable, undignified, or even emasculating.

Perhaps the most sinister aspect of the cycle of unwalkability, though, is how the voiding of walkers from the roads also voids the roads of witnesses. After all, even as night-time pedestrian deaths increased 96 percent 2009 and 2017, hit-and-run deaths increased153 percent, with at least 86 percent of those deaths occurring after the sun went down.

In 2009, 17 percent of walkers who died in America were abandoned in the street by the drivers who struck them, often delaying access to critical medical care that might have saved their lives. In 2021, it was 24 percent. And with no one around to witness their violence, personal injury lawyers claim that fewer than 10 percent of hit-and-run drivers are ever caught.

The Times writers are absolutely correct that battling America’s pedestrian death crisis will take an aggressive, multi-pronged approach, particularly after dark. They are wise to break that problem into pieces and focus on the structural factors that we can solve through policy, rather than the impossible project of convincing millions of human beings to never make mistakes.

It’s important to remember, though, that reversing a vicious cycle can be far more difficult than halting a trend. We don’t just need to install streetlights, redesign roads and cars, disable cell phones when their owners are behind the wheel, and give the poor the mobility and housing options they need to keep them out of harm’s way. We also need to rebuild a culture of walking in a world wheremany people have bought into car culture so deeply and so literally that they will fight to keep the world as it is.

We have our work cut out for us – which is why it’s important than ever that we’re shining a light on this critical issue in all its complexity.

source https://usa.streetsblog.org/2023/12/11/the-other-reason-american-pedestrian-deaths-are-rising-after-dark

Comments

Post a Comment