States, We Need Your Vision to Get to ‘Zero’

A version of this article originally appeared on Vision Zero Network. Read the original here.

As local, regional and tribal communities in the U.S. commit to Vision Zero in record numbers, the national Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and stepped-up federal strategies are bringing more funding and attention to safe infrastructure and public transportation than ever. This is encouraging, but we still need states to align their policies and funding decisions with these historic commitments. Because without state level change, the U.S. will likely continue to move in the wrong direction.

State DOTs play a central role in the safety and sustainability of transportation systems because states lead planning processes and set policies such as how speed limits are set and whether equity is considered. States largely decide where funding goes. Right now, in most states, funding priorities are not aligned with safety and sustainability goals.

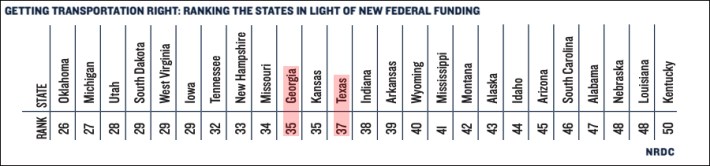

You can see how your state is measuring up in the new National Resources Defence Council Scorecard: Getting Transportation Right: Ranking the States in Light of New Federal Funding. The Scorecard ranks state planning for climate and equity, vehicle electrification, expansion of transportation choices, system maintenance and procurement. Georgia and Texas rank toward the bottom in the NRDC Scorecard — with Georgia at 35th and Texas two slots behind that.

Let’s take a closer look at why states need to do more — and at two states that could be models for success.

Texas

Texas leads the nation in traffic deaths, with one person dying every two hours on Texas roads. Vision Zero cities in Texas, including Austin, Houston and San Antonio, are being stymied by state restrictions on well-known safety best practices, including lowering speed limits, redesigning roadways and using speed safety cameras.

The increase in roadway deaths — and in driving overall — has gotten so bad that it inspired this Dallas-Fort Worth NBC investigative series – Driven to Death.

The series highlights two common vicious cycles: first, more auto travel lanes lead to more driving and higher speeds; then, higher speeds lead to more frequent and more deadly crashes. As the series describes, while tools to improve safety are proven and readily available, the Texas Department of Transportation continues to set speeds and design roads for speed over safety. As is the case in many states, city staff working to make streets safer face resistance from state leaders.

Much of this state resistance contradicts the U.S. Department of Transportation’s directive to design streets and set policies in ways that lead to safer behavior. For instance, the federal National Roadway Safety Strategy states “it is important to prioritize safety and moving individuals at safe speeds over focusing exclusively on the throughput of motor vehicles.”

Thanks in part to the National Roadway Safety Strategy and advocacy work by Vision Zero Texas, TxDOT is starting to consider changing speed policies. But the governor and state elected officials continue pushes to speed up travel. So as described in the NBC series, “state road design and speed limit rules actually contribute to higher speeds and more deaths.”

“We blame the users for using the system in the way it was designed,” said Jay Crossley of Vision Zero Texas, summarizing the NBC report. Nationally renowned urbanist David Zipper added, “At some point you have to make the choice of whether it’s more important to save lives or to facilitate fast car traffic.”

In the meantime, straightforward safety improvements on the most deadly roads in Dallas are stymied by these attitudes and TxDOT inaction. Many state leaders point to lack of enforcement as the problem, as does the head of the agency in the interview. This misses the point of using a Safe System approach, which focuses on upstream, preventative factors – such as designing roadways and setting speed limits to prioritize safety over speed – rather than relying on reactive, punitive measures such as enforcement.

Georgia

Like most state transportation departments, the Georgia Department of Transportation continues to prioritize speedy single-occupancy vehicle travel at the expense of safety and access for people traveling by walking, biking and transit. In addition to more roadway crashes and deaths, this also leads to serious negative climate impacts and harms the state’s budget.

Georgia’s low safety ranking is one of many reasons why the Peachtree State performs poorly in NRDC’s Transportation Scorecard. But there are well-known ways they can make their streets safer and improve their ranking while also improving the state’s climate resiliency and financial bottom-line.

Consider Decatur, a town of about 25,000 people just outside Atlanta, where a boy was hit and killed by a driver on College Avenue on Nov. 6, 2023 while walking to meet his mother. College Avenue is one of five state-owned roads that runs right through Decatur and has long been identified as a road needing safety improvements. These roads combine a deadly mix of high-speed vehicle traffic and high pedestrian activity.

Concerned about the dangers of walking, especially for the many students who walk to school along College Avenue, community members are calling for Georgia leaders to lower speed limits and add traffic calming measures to slow drivers down. Their petition for these improvements, which must be made at the state level, shines a light on a common problem in Georgia and throughout the country — and what must be done to reverse it.

California

California, by contrast, was the top ranked state in NRDC’s scorecard. The Golden State is making it easier to get around without driving, in part by advancing policies to better coordinate transportation planning with land use and climate goals.

For instance, California Senate Bill 375, passed in 2008, requires regional targets for planning entities to align plans with vehicle emissions reduction targets. Other recent state laws encourage infill housing development and eliminate minimum parking requirements near high-quality transit stops. California is also a leader in spending flexible federal transportation funds on public transit projects that promote affordability and clean air, although more work is needed to ensure that funds are not used for polluting and ineffective highway expansion projects.

At a minimum, states should give local and regional entities more control to address pressing safety, climate and equity goals. Much of California’s progress results from the State encouraging better planning — and then passing on funds to local and regional governments — which are often more willing to lead on climate, safety and equity goals. Other states would do well to pass more federal funding onto local jurisdictions to support clean transportation investments in safety.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts was ranked second in NRDC’s scorecard. The state is doing less on electrification and lower carbon procurement, but the Bay State is doing an admirable job of integrating the Safe System approach into its transportation policy. MassDOT uses a risk-based screening tool to quantify and address sites with the highest risks of fatal or injury crashes related to speeding. This is a prime example of using a more proactive, preventative approach, in contrast to waiting until tragic events occur to address problems such as high speeds and unsafe road designs.

MassDOT establishes target speeds and employs proven techniques to encourage lower and safer operating speeds to prevent serious injuries and fatal collisions. Rather than prioritizing wider travel lanes on high-speed roads running through neighborhoods, Massachusetts supports local jurisdictions’ work on roadway treatment for safe speeds.

Massachusetts has established design standards for pedestrian, bicycle and transit facilities that are applied to all projects. Massachusetts is also one of the growing number of states that incorporates more modern and relevant design standards. In 2014, it was the second state to endorse the NACTO Urban Street Design Guide, which better supports goals of increasing and improving trips made by bicycling, walking and transit.

Funding to do better

NRDC’s Scorecard shows that leading states, such as California, are also better stewards of an unprecedented infusion of federal dollars. Consider the the Vulnerable Road User Special Rule, which requires the 32 states whose vulnerable road user deaths exceed 15 percent of all fatalities to spend more of their state-controlled Highway Safety Improvement Program funds, the largest dedicated source of safety funding in the U.S, to address the safety of people biking and walking.

The amount each state must obligate is based on how much HSIP funding a state receives, ranging up to $46.1 million in Texas. According to the Federal Highway Administration, all states successfully obligated their VRU rule HSIP funding in 2023, resulting in $347 million obligated to projects that state DOTs say will improve bicyclist and pedestrian safety.

But pledging money doesn’t ensure that it will be spent on safety projects. In past years, 66 percent of HSIP funds were used on state-owned roads and less than 10 percent went to projects to improve bicyclist and pedestrian safety. Massachusetts is a leader in safety projects, while Texas and Georgia are far behind on this safety work.

Advocates and local leaders will need to continue to hold states accountable to making roads safer, as the federal allocations were designed to do. The League of American Bicyclists shares these helpful — and sobering — statistics by state. We encourage Vision Zero champions to monitor the types of projects funded and whether state-owned roads were addressed to ensure that funding is spent on safety as it was intended.

States must lead

Whether it’s lowering speed limits, re-designing roadways to encourage safer speeds, adding speed safety cameras, or other proven safety countermeasures; states are usually loath to make change, often citing such excuses as “We don’t have funding” or “That’s not the way we’ve done things in the past.” This can – and must – change.

Lately, more local jurisdictions are demanding changes at the state level to help communities be safer and healthier places to live. For example, Fremont, Calif. integrates state-level policy changes into its Vision Zero Action Plan, including gaining ability to use speed safety cameras and authority over speed limit decisions.

It is time for these sorts of changes to the status quo in all 50 states, whose leaders have outsized influence on what happens – or does not happen – for safety on our roadways, sidewalks, and bikeways. And if states don’t step up, they should step out of the way to allow locals and regions to address these challenges themselves.

source https://usa.streetsblog.org/2023/12/26/states-we-need-your-vision-to-get-to-zero

Comments

Post a Comment