Fuzzy Math: How Governments Decide a Harmful Highway Is ‘Worth It’

Advocates in Portland are debunking the economic justifications behind one of the nation’s most notorious highway mega-projects — and their efforts are offering a rare glimpse into the rat’s nest of errors, assumptions, and perverse incentives that underlie similar efforts across the country.

Recently, advocates with No More Freeways delivered an explosive letter to the Federal Highway Administration and the US DOT Inspector General, urging the agencies to “take no further action to advance the proposed Interstate Bridge Project” until the state DOTs in Oregon and Washington can prove, essentially, that the project isn’t setting fire to a giant pile of taxpayer money.

“Concretely, in economic terms, this is a wasteful, value-destroying project,” the advocates wrote. “Roughly speaking, it costs $2.50 to deliver just $1 in value to users of the facility. No More Freeways calls on FHWA to carefully examine the benefit-cost ratio of this project, and to reject the proposed application for federal funds.”

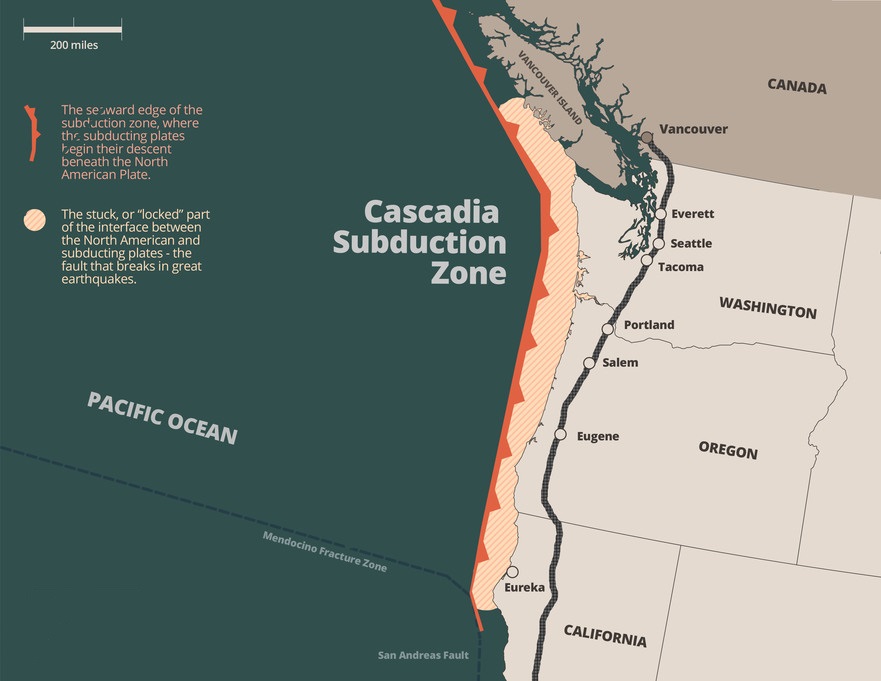

The single most expensive project on the U.S. Public Interest Research Group’s 2023 list of highway boondoggles, the seeds of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project were planted more than 17 years ago when transportation officials began exploring their options to replace an aging crossing over the Columbia River, which officials feared would be vulnerable to collapse if the long-forecasted Cascadia earthquake hits anytime soon.

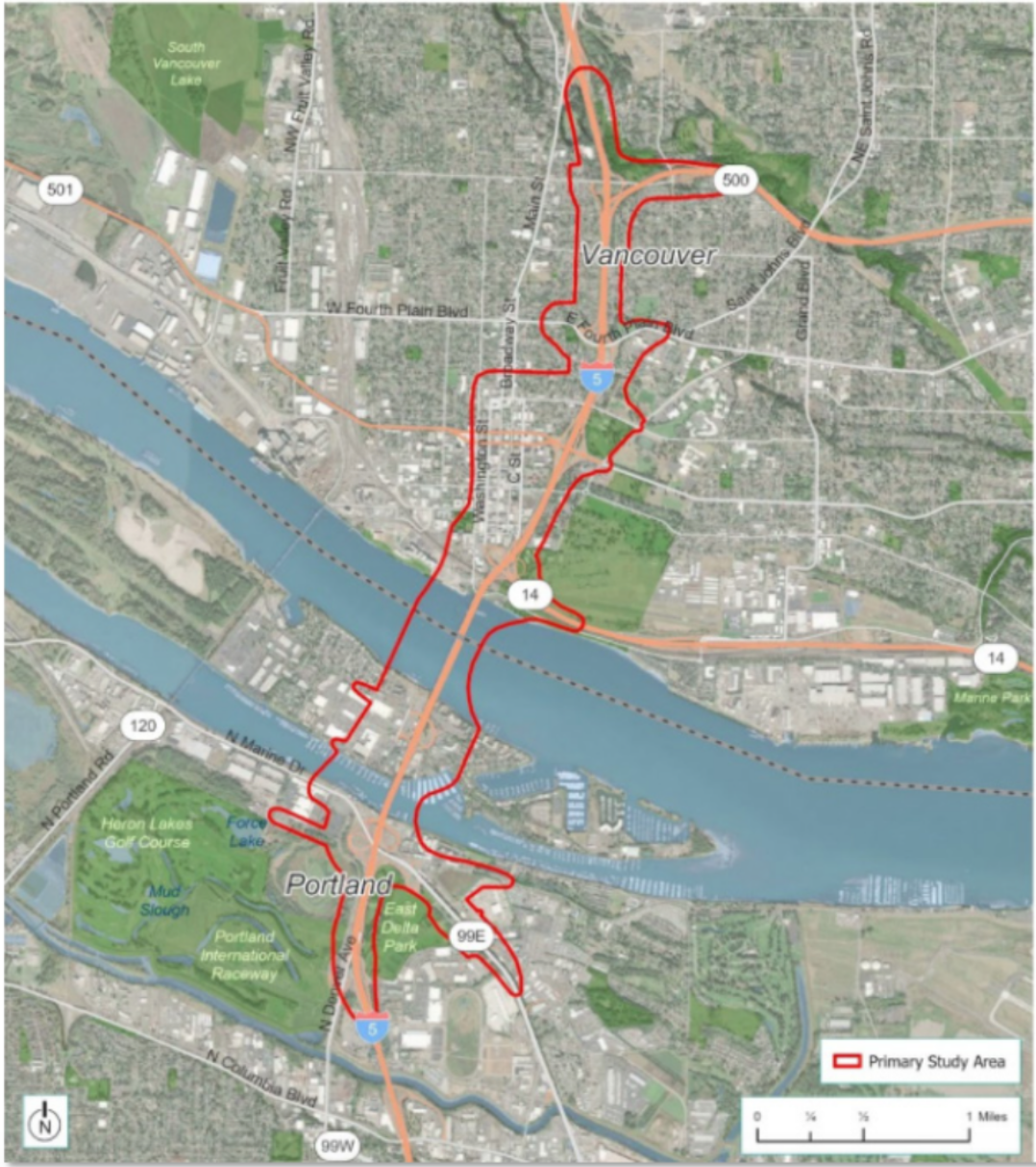

In the years since, though, estimates for the effort have ballooned to between $5 and $7.5 billion, with most of that budget devoted to expanding and reconfiguring I-5 leading up to the bridge to accommodate as many as 12 lanes, rather than reconstructing the aging structure for which the initiative is misleadingly named. Currently, much of I-5 has just six lanes.

“I think there’s very little resistance in Portland to just replacing the bridge before the Big One hits,” said economist and advocate Joe Cortright, who led the analysis. “And if that’s all they were doing with this project, I think would have happened a long time ago, and at a lot lower cost. But the state DOTs are using this as an excuse to rebuild and widen five miles of freeway and to rebuild seven highway interchanges … most of the cost of this project comes from a freeway widening that doesn’t produce many, if any, benefits.”

Freeway math

According to the sponsors of the project, though, the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project would create substantial public benefits — at least in the head-scratching world of Freeway Math.

Cortright explains that in order to qualify for federal funds, highway projects like the IBR have to perform what’s known a “Benefit-Cost Analysis,” or BCA, proving that every dollar they spend will generate at least one dollar in benefits for the public at large. And while BCAs can’t comprehensively account for everything that highways cost us, they do calculate their value in many different ways, including the economic value of the hours drivers might spend working instead of stuck in traffic, the quantity of emissions and fuel loss they’d avoid by not sitting in gridlock, and even the dollar value of human lives that might be saved by making road design changes to avoid crashes.

Predicting the future, though, is far from an exact science — and some advocates say the formulas DOTs use to do it tend to make freeway projects look more valuable on paper than they actually turn out to be.

In the case of “traffic time savings,” for instance, agencies utilize congestion prediction models that studies show tend to massively over-estimate future car travel as populations grow — so much so that some legal experts have called those models “junk science” and questioned whether courts and planning boards should accept them at all.

And when those junk formulas inevitably forecast future traffic delays, all that “lost” time is multiplied by millions of drivers and billions of dollars in “lost” wages (as well as fuel, vehicle wear-and-tear, and other costs) that they’ll collectively forfeit if they arrive even a moment late to punch the clock, producing stunningly large numbers that agencies argue could be “saved” by expanding the freeway.

The trouble is, a hundred years of research on the phenomenon of induced demand has shown that expanding freeways doesn’t cut congestion – it encourages it. And even if it did, it wouldn’t necessarily save drivers any money at all.

In the case of the Interstate Bridge Project, Cortright says that agencies estimate an average of just 20 seconds in time savings on the average five-mile trip. And based on that estimate, the BCA calculates that expanding the highway would, magically, put $2.4 billion back in residents’ pockets, even if most drivers just don’t value a saving few extra seconds stuck in gridlock all that highly —and their willingness to sit in traffic rather than pay tolls suggests a lot of them don’t.

“It’s far from clear that saving anybody 10 or 20 seconds on an individual trip has any economic value at all — even if you can multiply that 10 or 20 seconds times 150,000 people a day times 365 days a year times $18 an hour to gin up some really big number,” he adds. “It’s just not clear that people value travel time savings of those very small amounts; it’s not even clear that they that would even recognize that there even was a travel time savings.”

Convenient mistakes and bad assumptions

Cortright says, though, that the project isn’t just suspicious because it relies on flimsy freeway math. Because in many cases, he says, the authors behind the BCA actually got the math wrong in ways that make the project look more valuable than it really is — and if they did so deliberately, he argues, they essentially slipped a few extra winning cards into an already-stacked deck.

When estimating the value of travel time cost savings, for instance, the agencies deviated from federal guidance and overestimated how often drivers will carpool on the newly-widened highway, a mistake that would reduce those benefits by a staggering 11 percent if corrected. And they also ignored the fact there’s a second bridge across the Columbia running parallel to I-5 just a few miles away — and didn’t account for all the money drivers who took that bridge rather than pay the I-5 toll would “lose” as the free crossing became more congested.

When it comes to safety, Cortright says the BCA calculated a 17-percent drop in crashes based on an incorrect use of a formula designed primarily for rural highways with no traffic lights on their on- and off-ramps to minimize dangerous merges. And again, agency officials basically ignored the existence of the nearby bridge where crashes might rise as drivers change their routes.

Perhaps most gallingly, though, Cortright says the analysis over-estimates the probability of the harrowing Cascadia earthquake striking the highway during the lifetime of the expanded highway, as well as essentially assuming an extreme, worst-case scenario where that disaster would cause the bridge to completely collapse during heavy traffic and kill almost everyone driving on it. Cortright says the report authors even inflated the length of the bridge itself, thereby inflating the economic value of the lives that would be lost on it by a factor of ten — and also added hundreds of millions of dollars in additional “travel time costs” by assuming, incorrectly, that drivers would clog up every other road in the region when the bridge went down, rather than taking other modes or even just staying home.

“[The bridge collapsing] is absolutely a real risk — no doubt about it,” Cortright stressed. “But they made [an estimate] based on a set of assumptions that gives you this very inflated value for the number of people who would be at risk during the seismic event. … [And they’re also predicting] it’ll be a Carmageddon situation, which just isn’t what tends to happen.”

Cortright says some of those errors could be honest mistakes on the part of WSP, the firm which prepared the analysis of behalf of the DOTs. Considering that WSP has already secured $76 million in consulting contracts on the project should it go forward, though, he suspects the errors weren’t all innocent — especially since the firm’s gargantuan conflict of interest was not disclosed.

“They’re not an independent or objective analyst of benefits and costs. … They have reasons to put their thumb on the scale and make it come out a particular way,” he adds.

Knowingly submitting false information about highway projects to the federal government is a crime punishable by fines, up to five years in prison, or both.

Unstacking the deck, rethinking the dealers

Cortright acknowledges that unraveling the Gordian knot that is a highway project Benefit Cost Analysis isn’t for the faint of heart, even for a professional economist like him. He says, though, that systemic reforms could someday force agencies to be more honest with the public about the real benefits of autocentric mega-projects — or, more accurately, their devastating costs.

For one, US DOT could require grant applicants to use better formulas to forecast the congestion impacts if their projects get built, incorporating decades of research on induced demand as well as how much drivers are actually willing to pay to avoid sitting in traffic. And if they were, advocates say many of the on-paper safety, emissions, and congestion “benefits” of highway expansions would likely vanish.

Unstacking the deck, though, won’t be as impactful if the dealer still gets a multi-million dollar cut when the house wins. That’s why Cortright suggests that BCAs should face more federal scrutiny — or, at the very least, the people who stand to benefit from fuzzy freeway math shouldn’t be allowed to prepare them.

“It makes no sense that a private consultant who has an interest in the outcome gets to write the benefit-cost study,” he added. “And for that matter, it doesn’t make sense for [a state highway department] to do it, either. If you’re going to do a benefit cost study, it ought to be done by somebody who has no interest one way or the other in whether the benefit cost ratio comes out at one level or another… In a sense, the process is a sham.”

source https://usa.streetsblog.org/2023/12/14/how-governments-decide-a-harmful-highway-is-worth-it

Comments

Post a Comment